In recent years, countries across the globe have implemented laws to mitigate plastic production and pollution.

In the past two years, both large developed nations like Australia and smaller developing countries like Sri Lanka and Belize have passed ambitious national laws to phase out a number of plastic products like bags, cutlery, and straws.

But the U.S., a leading producer and consumer of plastics, remains woefully behind, even as it stands as one of the world's biggest polluters. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the country produced 35.7 million tons of plastic waste in 2018, more than 90% of which was either landfilled or burned. The U.S. ranks second in the world in total plastic waste generated per year, behind only China — though when measured per capita, the U.S. outpaces China. In 2019, the U.S. also opted not to join the United Nations' updated Basel Convention, a legally binding agreement aimed at preventing and minimizing plastic waste generation that was signed by about 180 other countries.

More than 90 countries have established (or have imminent plans to establish) either bans or fees on single-use plastic bags or other products, according to data from the non-profit ocean conservation organization Oceana. The U.S. is not one of them. Though Americans have been aware of plastic pollution as an environmental concern as early as the mid-20th century, U.S. action against plastics has been piecemeal — the federal government has left it up to individual cities, counties, and states to decide whether and how to regulate plastics.

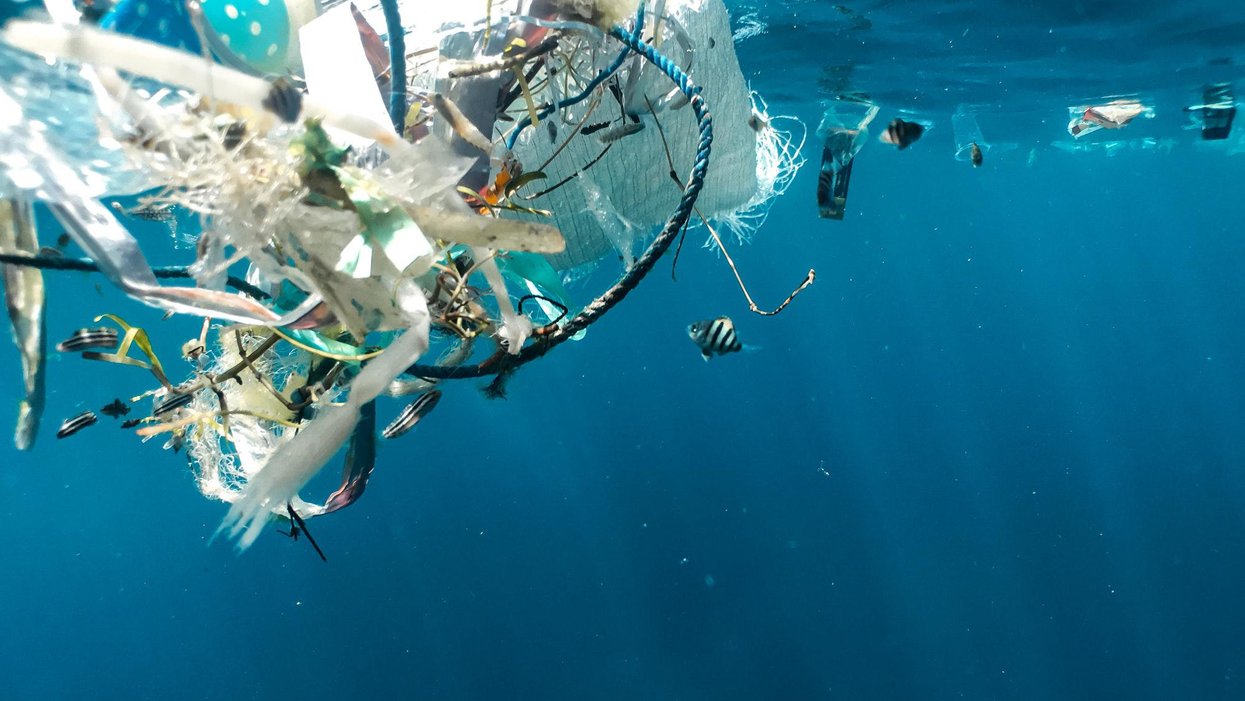

The plastic problem is growing increasingly urgent. More than 1 million plastic bags are used every minute, with an average "working life" of only 15 minutes. Experts believe the ocean will contain one ton of plastic for every three tons of fish by 2025 and, by 2050, more plastics than fish (by weight).

Not only does the ocean (and all life reliant on it) suffer from plastic pollution, but human health is also at risk. Microplastics have well-documented impacts on human health, and have been found in 90% of bottled water and 83% of tap water. Our incessant plastic consumption is cultivated by "throwaway" culture, fueled by the plastic and oil and gas industries' efforts to sustain high plastics consumption while distracting people with recycling campaigns.

This story is also available in Spanish

However, a new proposed federal bill—the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act—offers potential solutions, and could transform the U.S. from a hindrance to the global movement against plastics into a much-needed ally. Such federal action could help stop the fractured approach to tackling plastics in the U.S., and shift the burden from consumers to plastic manufacturers.

Advocates say even if the bill doesn't pass in full, its component parts, especially those that are more bipartisan, could likely peel off and be recycled into other legislation. For example, a part of the bill addressing plastic pellets, or "nurdles," has already broken off and become its own piece of potential legislation, the Plastic Pellet Free Waters Act.

U.S. lags behind plastic pollution regulation

The European Union passed a comprehensive directive a couple of years ago. (Credit: campact/flickr)

Other countries not only produce less plastic than the U.S., but they've also more successfully legislated against plastic pollution. The European Union passed a comprehensive directive a couple of years ago, for example, that requires member countries to ban a slew of single-use plastic products, collect plastic bottles for recycling and reuse, and label disposable plastic products appropriately, at minimum. Many countries are going beyond those requirements.

In Canada a federal ban on plastic bags, stir sticks, ringed beverage carriers, cutlery, straws, and food takeout containers made from hard-to-recycle plastics is set to take effect at the end of the year.

It's not just Western or "wealthier" nations who have successfully implemented measures against plastics. Dozens of countries across Africa, Asia, and Central and South America have legislation in place to quash the single-use plastic crisis.

Christy Leavitt, the U.S. Plastic Campaign Director at Oceana, told EHN that the EU directive is just one example for the U.S. to emulate. Oceana has surveyed countries around the world, taking inventory of the global anti-plastic legislation and assessing where the U.S. sits comparatively, and found progressive policies in many pockets of the world.

"Chile passed what is, if not the most comprehensive, one of the most comprehensive single-use plastic foodware policies in the world," Leavitt said. Beyond banning single-use bags and straws, Chile prohibits all eating establishments from providing single-use cutlery or containers. Grocery and convenience stores must also display, sell, and take back refillable bottles, creating a cyclical system of bottle reuse.

As early as 2002, the East African country Eritrea banned plastic bags in its capital city Asmara. The country implemented a nationwide ban on the import, production, sale, or distribution of plastic bags in 2005. Rwanda banned plastic bags in 2008 and then all single-use plastics in 2019, with heavy fines and even jail time for anyone found importing, producing, selling or using single-use plastic items.

When countries across the globe with fewer resources than the U.S. successfully push out harmful plastic products, it gives the U.S. no excuse to be so behind, Leavitt added.

What plastic pollution regulation exists in the U.S.?

In the absence of national legislation in the U.S., local governments at the city, county, and state levels have regulated plastics. As a result, there is a diverse set of mandates and ordinances scattered across the country.

One paper in the Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning says that "as of August 2019, eight

U.S. states, 40 counties, and nearly 300 cities had adopted policies that, either through a ban, fee, or combination thereof, aim to reduce the consumption of single-use plastic bags."

To Rachel Krause, a public administration researcher at the University of Kansas and author of the paper, it's curious to see such a large issue relegated to local governments. "We tend to say that policy responses should be at scale or in proportion to policy problems," she told EHN, "but local governments aren't at scale with climate change, local governments aren't at scale with global plastics. And yet, in a lot of places in the United States, that's where we're seeing the action happen."

Local action against single-use plastic, by definition, has limited reach and is less efficient than sweeping national policy would be. Ordinances at a city or county level are also prone to being struck down by statewide preemption laws, when states ban local governments from taking action.

Eighteen states have some sort of preemption law in place. In Texas, for example, individual cities like Laredo tried to implement plastic bag bans, but the Texas Supreme Court knocked them down in 2018, saying they conflicted with state solid waste management laws.

That said, "the amount of just individual pieces of legislation that have been introduced at the state and local level, in the last five years has, increased by an order of magnitude, maybe more," Alex Truelove, the Zero Waste Campaign Director with U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG), told EHN. The legislative landscape felt so much more sparse just a few years ago, Truelove added — a great sign, since the more states engaging in anti-plastics discourse, the harder the issue is to ignore on a national level. Plus, "every time something passes, we learn something" about what does and does not work.

The problem is "it's much easier to block something than to get something passed," University of Southern Maine environmental policy researcher Travis Wagner told EHN. This is especially true at the federal level. He added that the federal government explored possible legislation against plastics as far back as the 1970s, as bottle bills were adopted around the country.

"Bottle bills," also known as "container deposit laws," typically work by mandating small deposits on drink containers like plastic bottles and metal cans that customers can get back if they recycle those bottles. Oregon passed the first bottle bill in the U.S. in 1971, and by 1986, 10 states had enacted some kind of bottle bill into law (there are still only 10 states doing this to date). In the 1970s, Wagner said, it seemed like there was enough momentum to pass a national bottle bill, "but politically, it was just really, extremely difficult."

In the half century since the federal government first considered taking a national stance on plastics, the issue has only gotten worse.

Who is to blame for plastic pollution?

Historically, the conversation around plastic pollution in the U.S. has centered on individuals' and communities' abilities to recycle. (Credit: Brian Yurasits/Unsplash)

Historically, the conversation around plastic pollution in the U.S. has centered on individuals' and communities' abilities to recycle. But Leavitt said that recycling was an ideal pushed on the public by the plastics industry as "a way for [them] to put the blame of plastic pollution and the responsibility to fix it on consumers. And it worked. While we focused on recycling, industry exponentially increased the amount of plastic it produced."

The idea that it is the individual's responsibility to recycle, to not litter, and to buy less was so pervasive "that it's become embedded in our psyche," added Wagner. "That's the industry saying 'It's not us, it's you.'"

Meanwhile, records and reports from as early as 1973 suggest top industry executives knew that plastic recycling could never be successful on a large scale.

"It's all coming down to dollars and cents for the industry," Shannon Smith, Manager of Communications and Development for the nonprofit FracTracker Alliance, told EHN. "The misperception is that there's a demand for all of this plastic, and so the industry is just responding to the demand of consumers, where it's really the opposite." In reality, she added, there's an oversupply of fracked gas in the U.S., and one of the best ways to profit from all that supply is to generate more demand for plastic. "So it's totally industry driven."

Plastics are primarily made from the natural gas byproducts ethane and propane, which are turned into plastic polymers in high-heat facilities in a process known as "cracking." The U.S. is the world's leading producer of natural gas, with 30 cracker plants currently in operation and at least three more expected by mid-2022. To add insult to injury, Smith said, "the fracking industry has never been profitable," and petrochemical companies and facilities are actually the frequent recipients of government subsidies. "We're subsidizing them, we're paying for their ability to make a profit while they're sacrificing our health."

It's time to put the responsibility of managing plastic waste back on the companies producing it, Truelove said. "If f your bathtub is overflowing, the first thing you do is turn off the tap," he added.

Break Free From Plastic Pollution

Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR), pictured here, and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), introduced the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act. (Credit: merkley.senate.gov/)

A new piece of federal legislation seeks to turn off the proverbial tap. First introduced in 2020 and reintroduced in March 2021 by Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, if passed, would comprehensively address plastic production, consumption, and waste management in the country.

"The idea behind the bill was to really kind of assemble all of the best ideas from not just around the country, but honestly from around the world," said Truelove. The EU directive, for example, was a great precedent and a beacon for the direction the U.S. could follow, he added.

Congressman Lowenthal wrote to EHN that "this bill incorporates best practices and important common-sense policies. While it may be ambitious – it is by no means radical." The bill would ban single-use plastic bags and other non-recyclable products, include a bottle bill, and channel investments to recycling and composting infrastructure. "The legislation makes producers responsible for the end use of their own products," added Congressman Lowenthal. Producers of plastic packaging would be required to design and finance waste and recycling programs.

Truelove also mentioned that the bill, importantly, sets a minimum for states to abide by, allowing individual local governments to pursue or keep more aggressive policies —"we don't want to punish the states that have those stronger laws."

The proposed bill also includes components of environmental justice, requiring the EPA and other agencies to more rigorously study the cumulative environmental and health impacts of incinerators and petrochemical plants, while also placing a moratorium on new or expanding facilities. Frontline and fenceline communities — so named because they are situated next to these industrial plants, right up to the fences — are the most harmed by the poor air and water quality inflicted by the plastics industry. They are also disproportionately communities of color.

What is the future of plastics regulation?

The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act has not been put into law yet. It is currently co-sponsored by 12 other senators, but the timeline for when it might be passed is still very unclear.

Truelove is hesitant to make predictions, but he's optimistic that, in the long run, some form of federal legislation will pass. Wagner is more skeptical: "I am optimistic, but not at the national level." In his mind, individual states will continue to lead.

Though the full Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act has no clear path forward at the moment, pieces of the bill are already breaking off and being discussed more seriously. Lowenthal wrote that breaking off elements of the bill and integrating them with more narrowly focused legislation with bipartisan support, or attaching them to bills at the verge of being passed, is a practical move to get parts of the bill through Congress bit by bit.

"A lot of this work tends to be incremental. It almost has to be, by nature, just the way our institutions are built," said Truelove.

But even if the bill is passed, it's still no panacea. The plastics and petrochemical industries will likely continue pushing for what Truelove calls "false solutions," like chemical recycling innovations (where plastics are broken down again into polymers, effectively turning them into diesel fuel — a different environmental nightmare) or flashier anti-littering campaigns.

"What we're doing is an affront to [industry's] business model," he added. "You've got Dow, DuPont, Chevron, Exxon, and so on...and they're incredibly powerful organizations with a lot of political influence." To substantially move towards less plastic production and more reusable products, the government will need to push past those distracting pseudo-solutions, even when they seem like they could be profitable.

"It's totally doable," said Truelove. "I mean, I think if we can get to the moon, we can figure out how to make it easy for people that have reusable foodware or reusable packaging for shipping."

Banner photo credit: Naja Bertolt Jensen/Unsplash

- Scientists: US needs to support a strong global agreement to curb plastic pollution - EHN ›

- Scientists: US needs to support a strong global agreement to curb plastic pollution - EHN ›

- The Titans of Plastic: plastics industry in Pennsylvania - EHN ›

- Chemical recycling and its environmental impacts - EHN ›

- Chemical recycling and its environmental impacts - EHN ›

- Lawsuits against the plastics industry for health and environmental harm could exceed $20 billion by 2030 - EHN ›

- Pete Myers to address US Senate committee on the dangers of plastic - EHN ›

- Lawmakers push Biden administration to act faster on plastic pollution - EHN ›

- Every stage of plastic production and use is harming human health - EHN ›

- Recycling plastics “extremely problematic” due to toxic chemical additives: Report - EHN ›

- La contaminación por plásticos, explicada - EHN ›

- Chemical recycling “a dangerous deception” for solving plastic pollution: Report - EHN ›

- The chemical industry may have killed a landmark EU chemical policy. Here’s what that means for the US. - EHN ›

- LISTEN: Investigating BADGE, BPA's evil cousin - EHN ›

- California avanza con una ley histórica de reducción de residuos plásticos - EHN ›

- California moves forward with landmark plastic waste reduction law - EHN ›

- Around the US, illegal dumping creates mental health challenges - EHN ›

- This will be a big year in shaping the future of chemical recycling - EHN ›

- Plastic chemicals are more numerable and less regulated than previously thought - EHN ›

- Proposed bill seeks to ban single-use plastic foam products in US - EHN ›

- Zero- and low-waste businesses band together against plastic pollution - EHN ›